How I Started As A Concert Photographer

One of the most underrated things about being a concert photographer is meeting fans right in front of the stage when you're behind the photo barricade waiting for a set to start. Since the only fans you meet in that position are the ones passionate enough to be there hours before doors open to get right up on the rail, it’s nothing but interactions with superfans across the board. And because you’re interacting with musical superfans of one kind or another, there’s one question that comes up over and over again:

“How can I do what you’re doing?”

Believe me, it’s come up enough that I’ve toyed with having a pamphlet printed out to whip out of my back pocket and hand them right as the headliner hits the stage, with a wink and a half-smile, knowing the rest of their life has been changed.

But then I remembered the only people dealing in pamphlets these days are political candidates and Scientologists…so how about this instead?

Can I give you a step by step process on how to become a concert photographer in the next year? No. Well, maybe (man, I’m really selling this aren’t I?). What I mean is, I can tell you what I did to get where I am, but those steps and opportunities may not be exactly the same depending on things like geography, etc. But one of the things that really helped me out when I was first getting into this world was the advice of more experienced photographers than myself, so hopefully this can be that same kind of resource to someone else.

If “how can I do what you’re doing?” is the most common question I hear in my music photography journey, “what kind of camera do you need?” is probably a close second. And here’s the way that conversation usually unfolds:

- Photographer answers with the kind of camera/lens they’re using

- Person looks up what the cost of that camera/lens combo is

- The price most likely starts in the hundreds and can easily be in the thousands of dollars

- Person thinks “oh well fuck this” and that’s the end of it

I get it. For a lot of us, photography is a very expensive hobby that can occasionally bring in some money at irregular intervals. The barrier for entry can be pretty high. One of the only reasons I was able to get into photography initially was because it started as a COVID lockdown hobby that I was able to afford largely because I wasn't going anywhere or doing anything. If you want to get a Sony or a Canon or a Nikon, it might cost a pretty penny, even if you buy used and hunt for deals.

But don’t let that stop you! As much as it may not excite the budding concert photographer to hear the old saying “the best camera is the one you have on you”, there’s a reason that’s been a saying for however long it’s been a saying (I’m not a historian nor am I getting paid for this so just deal with it). My first two years of photography (including my first ever time shooting a band) were on a Lumix G7, which you can usually find used with a lens thrown in for about $300 - $350. And as un-sexy as it sounds, you’ve got your phone on you. It’s got a camera in it. Use it. No, it’s not as “nice” of a finished picture as you’ll get from a proper mirrorless, but modern phone cameras can really put some work in. And a lot of them shoot in RAW format, which will let you edit them in something like Photoshop or Lightroom and really get them looking a cut above your average iPhone snap.

Not trying to toot my own horn or anything, but I went to a Papa Roach show last summer where no non-phone cameras were let in, not even point-and-shoots. I was able to shoot these pics with an iPhone 13 Pro:

Again, nothing that’s going to break the world of live music photography in half, but a good example of what you can do with the camera that’s always on you. And that’s a ‘worst case’ scenario.

But if you’re going to be serious about concert photography, you’re going to need to get a proper camera eventually, as most established acts at medium-to-large sized venues won’t approve photographers using just their phone camera. Buy used. Surf eBay and Facebook Marketplace. Hell, there are services that will let you rent out really nice equipment for pretty cheap if you want to test out a potential camera/lens system before committing to buy.

So now you’ve got your camera. How do you get Taylor Swift to call you and ask you to cover her upcoming show?

Don’t worry…you’ll get there. But you’re probably going to have to start a little smaller. This is where geography can come into play like I mentioned. When you’re first starting out, you’re most likely going to have to shoot whatever live music is available to you. Because I live in Chicago, there’s a ton of live music going on in the city every night of the week. The kind of places that don’t require a photo pass for someone to come and take pictures of a show (bars with a stage, smaller venues) are a goldmine for a beginning concert photographer. And in a big city like Chicago, there are more of those opportunities at those kinds of venues than any one photographer could possibly cover. If you live somewhere that’s a bit further out from that kind of metropolis or doesn’t really have a lot of live music venues around, it might be a little tougher. I know I’m spoiled by the amount happening in my city on a nightly basis, and recognize how much that kind of supercharged how quickly I was able to do some of the things I was able to do in 2023.

The good news? It really doesn’t take a whole lot of shows to put together your first portfolio. When I first started pitching myself directly to bands and to publications (we’ll get to what that is in a minute), my entire portfolio was:

- One band I shot at a venue that doesn’t care if you bring in a camera

- Four bands from one show I shot at another venue that lets anyone that buys a ticket bring in a camera

- Pictures that I took from the crowd at Riot Fest, a 3-day rock festival that lets ticketholders bring in any point-and-shoot camera that doesn’t have a removable lens

That’s it. Crowd pics from a fest and 5 individual bands, all shot from the audience side of the barricade. But that was enough! I was able to sell myself to a publication with only that portfolio, who then sold me on my first show approval based on that same portfolio. Five bands and some crowd shots! It really doesn’t take a ton!

So I’ve dropped the word ‘publication’ on you a few times now without much explanation. If you’re really looking to get into concert photography, you’re going to encounter that phrase sooner or later. A publication is basically any media outlet that writes about music. Rolling Stone and Pitchfork are publications. But the majority of publications are very small and are essentially specialized blogs. But what a publication can give you, especially if you’re a beginning photographer, is credibility to a band’s PR.

Like, let’s say Metallica is coming to your city and you really want to shoot their show. If you’re just a photographer with no publication backing you up, what are you offering to the band’s PR in exchange for giving you a photo pass? Give the band the pics? Metallica has more than enough pictures of every single show they perform. They don’t need more from you, even if you’re super great at what you do. But if you have a publication? Now you’ve got something to offer to PR: COVERAGE.

Exactly what ‘coverage’ is can vary depending on the publication. Most commonly, it’s a review of the concert itself alongside an image gallery from the show. Some publications only require a paragraph or two as the written portion, some require a full fleshed-out review. But you have to have something published and live on a website in exchange for the ticket and photo pass you get for the show. Your Instagram account does not count as a publication.

“But Rich,” you say, “I got into this to take pictures. No one said anything about English homework.” I know, I know…the writing part is the less fun part for a lot of people. Some photographers straight up hate writing. But the majority of publications out there require it, so if you think you’re going to be involved with a publication at some point, start brushing up on your writing now. But there are some major upsides! The first is that it’s not hard to make your coverage stand out from a lot of what’s out there. Bring some personality to your writing and try to elevate it above the standard “...and then the band played (insert big hit) and the crowd went wild and sang along every word”. My personal philosophy is that if someone is going to use their tame to write something I wrote, I better make damn sure it’s interesting enough to make it feel worth their time. As long as you can say you did that, what you wrote is quality and will be noticed.

The other upside of having a publication behind you? If you don’t have a lot of experience, you can essentially lean on their seniority to get approved for shows. The second show I ever requested a photo pass for was for the band Our Lady Peace. Yes, their biggest days may have been a few decades ago, but it’s still a band that’s sold 5 million albums worldwide and the show was at a House of Blues, not some rinky-dink bar. At that point, I had only shot one concert from a proper photo pit, but the publication that was requesting on my behalf (Music Scene Media) was two years old and had a very visible history of being approved for major artists. They vouched for me, so I got the approval despite not being the most experienced guy in the pit.

But let’s say you haven’t been able to hook up with a publication quite yet. Or maybe you have, but you haven’t heard back from the headliner’s PR for a concert you want to cover. You’ve still got options! Reach out to some of the opening acts on social media and ask if they want coverage. Some will be open to giving you a photo pass just for a few pictures they can use. But if you can promise a written review that will include them, something that smaller opening bands can sometimes struggle to get, that is something that will catch a lot of bands’ eye.

And that’s basically it! Try the things I’ve outlined above and by the time you get to this point, you should be well on your way. But that doesn’t mean you’re off the hook from my rambling. Far from it! I’ve got some bits and pieces and loose ends and advice that I’d love to impart to all you beginners that didn’t fit anywhere yet, so they get their own place here:

- Be nice to everyone. Other photographers in the pit and around the venue. Security, box office, and other venue workers. Any musicians you might cross paths with. It’s not hard and it’ll only pay off over time. Be supportive of other photographers and share their work if you think it’s awesome. I know that sometimes it can be hard to break the ice and introduce yourself to photographers you don’t know, but you have the ultimate ice breaker: YOU BOTH LOVE CONCERT PHOTOGRAPHY! Just start there! Have you shot this band before? Have you shot this venue before? Do you have an Instagram I can follow? That last one is the one I use the most, even though it makes me feel stupid every single time. Of course they have an Instagram. They’re a photographer. But I still feel like I need to ask because just blurting out “Give me your Instagram” feels unnecessarily aggressive.

- Shoot every band on the bill if you can. Yes, the headliners are the sexy draw and some publications may only require you to cover the headliner, but like I said, the opening bands are the ones that can really appreciate the photos and review. Some of the first paid gigs I received as a concert photographer were from local bands I covered as openers for some of my first shows that were playing another show (sometimes as headliners) and remembered me from my initial coverage.

- If you don’t have a bevy of lenses at your disposal, I would rank lenses the following way as far as priorities to get over time:

- 24-70mm: for most small to mid-sized venues, this can probably cover 90% of what you want to do. If you’re shooting in places that don’t require a photo pass, they’re probably small enough that this lens should be all you need. And if you are getting approved for photo passes, this should cover most of what you want to do from the pit.

- 17-28mm: Even in small venues, you might need to go wider than 24mm to get shots of the entire band/stage at once. Great lens to also get pics that incorporate both the band and the audience.

- 35mm: Zoom lenses are fantastic and versatile, but if you’re first starting out, there are going to be some venues where the lighting just suuuuuucks. And in those venues, you’re going to need a prime lens that can go to a f/1.4 or f/1.8 to let as much light in as possible. It may seem weird for me to recommend a 35mm when, if you’ve followed what I’ve said so far, you already have that focal length covered with a 24-70mm lens. And I almost recommended an 85mm lens for that very reason. But sometimes if you’re in the pit or at a smaller venue, you might be too close for a 50mm lens. You can always crop in if you’re further away than you want to be, but you can never crop out if you’re closer than you expected.

- 150-500mm/200-600mm/100-400mm: Yes, it is ABSOLUTELY a luxury to have a zoom lens with some real reach. But once you have one, it opens up so many windows. You can shoot ‘soundboard’ shows (essentially shooting at an amphitheater or arena from the soundboard, which can be quite far from the stage). At a bigger venue, you can continue to get awesome pics of individual band members from the front of house (aka anywhere that’s not the photo pit). Which brings me to my next piece of advice…

- Post your work everywhere! One of the coolest things that happened to me last year (and also in my entire life) was a record label contacting me out of the blue asking if they could pay me money to use pictures I took at a concert for a vinyl release of that show! The boxed set comes with a hardcover photo book and my pics are going to appear in it! When I say they contacted me out of the blue, I really mean it. I have no idea how they found me. I had my review of the concert with the photos on my publication’s website, but I also posted some of those pics and a link to the review on the band’s subreddit as well as on their (very active) Discord channel. One of those two channels might also have been how I got my work on their radar. Either way, it paid off!

- Set goals, but don’t measure your success only by those goals. For 2023, my goal was to get approved to cover Riot Fest in Chicago as official media. To do that, I had the secondary goal of shooting at least 2 shows a month to make sure that by the time press applications opened, I had a decent portfolio to offer up. That goal didn’t end up fulfilled as I did not get approved to cover Riot Fest, but in the process of covering so many shows to make my portfolio as impressive as I could, I had shot some of my absolute favorite bands and had gained a ton of experience in a field that I was still relatively new to. It was a bummer not completing my goal, but the work I got done along the way was head and shoulders above anything I thought I’d be able to accomplish that year.

- Shoot your shot! There are only three things that can happen if you request to cover a show that you might think is out of your league: you hear nothing, you hear ‘no’, or you get a ‘yes’. Those first two are the same outcome and exactly where you would be if you didn’t reach out anyway, so honestly what’s the harm? You’d be surprised how many smaller publications can get approved for pretty big shows!

- Figure out what you want out of it. Do you want to tour with a band? Become a house photographer for a venue? Get paid working the local scene? Do unpaid work, but being able to cover major shows for your favorite bands? You don’t necessarily need to have a specific goal like that (or limit yourself to just one of those things), but if you do know what some of the end goals are, it’s easier to do the kind of work and make the kind of connections that will push you in those general directions as you continue to cover shows.

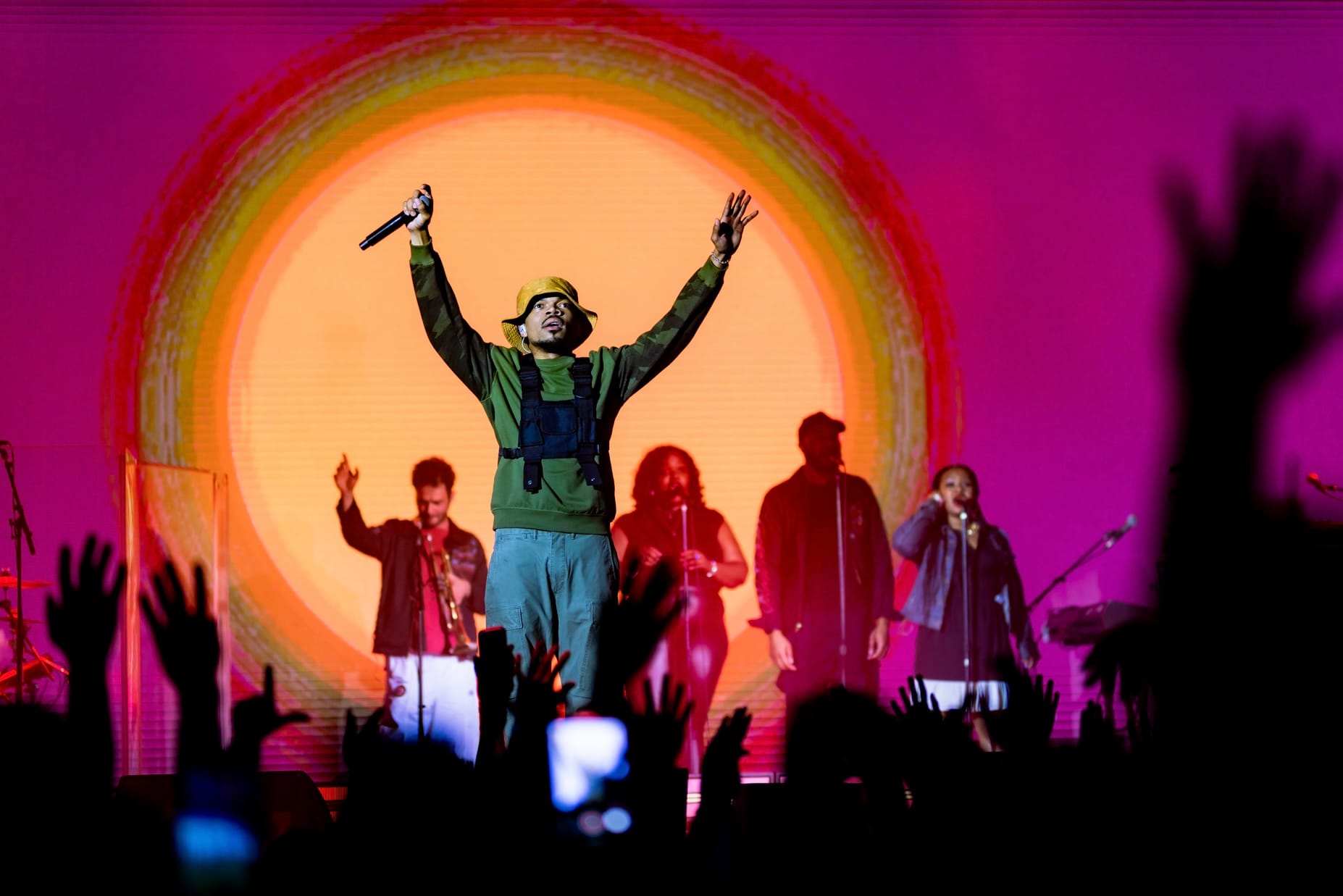

- Shoot from front of house if you’re allowed to. Sometimes you get approved to photograph a show, but you get the first 2-3 songs from the photo pit and then THAT’S IT. Nothing from front of house/moving around the rest of the venue. And that can be a total bummer because most of the best lighting and pyro and stage productions happen later in the show. So if you are allowed to continue shooting from the crowd after you’re out of the pit, I very much encourage you to do so. It may not feel as glamorous, and sometimes might be a little tougher to operate from general admission, but I’m always surprised how many of my favorite images from shows I’ve covered are from front of house. I think seeing all the hands and phones framing the bottom of your pictures that really give them an energy that you can’t quite get shooting from right up against the stage.

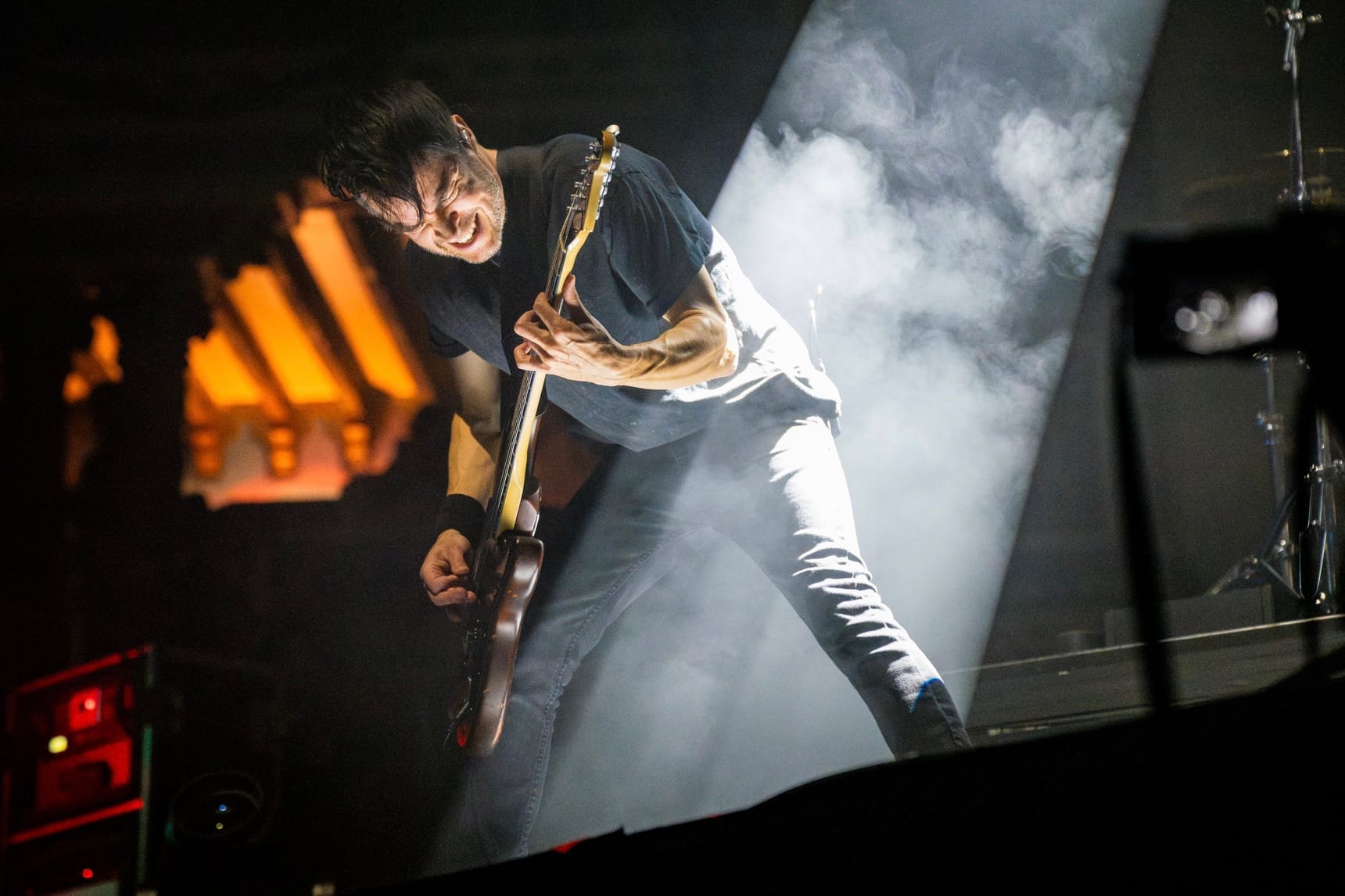

Like, I like this pic:

But this one captures the feel of the show so much better in my mind:

(And it was shot on a 150-500mm lens from the back of the venue I was in, so I don’t just spout random bullshit at you about the usefulness of ultrazoom lenses, I really do these things myself!)

So here’s the other thing…it’s only been a year and a few months since my first official approval to shoot a concert, so I don’t have anywhere close to all the answers. This is just what I feel like was most helpful to me over the last year and hopefully it was helpful to some other young me out there getting his start. And if anyone has any questions about anything, my Instagram is @richfunkphotos and I’m always around to answer questions or give advice.